Adopted in order to pursue foreign policy objectives, financial sanctions have become a source of increasing difficulty for financial institutions over the past few years. The ever growing number of applicable regimes tied to the international agenda is now also coupled with tighter enforcement measures. The opening on 31 March 2016, of the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) in the UK, is but an additional indication of the significance of the matter, and of the desire of the authorities to have these sanctions clarified, implemented, and enforced.

By Gerard Kreijen, Bert Gevers and Olivier Coulon, 7 June 2016.

The sources of complexity are numerous. On top of the list: the number of different regimes, the fast changing legal environment, and the broad (some would say ‘imprecise’) wording of the provisions.

Following this trend, the Luxembourg financial institutions, which were used to dealing with the AML (anti-money laundering) and CFT (counter financing of terrorism) acronyms, have also had to cope with the abbreviation FS (financial sanctions), more recently.

These regimes, although often seen as one group of international sanctions, are actually different. The objective of the rules concerning anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism is to ensure that funds from and/or received by clients are not the result of criminal activities or used for the financing of terrorism. On the other hand, the main purpose of financial sanctions is to avoid funds or economic resources being made available to listed persons, entities or institutions. This difference is of practical importance: screening mechanisms and software dedicated to one’s compliance with the anti-money laundering and counter financing of terrorism regimes may not be sufficient to ensure full compliance with the financial sanctions rules. The inadequacy of these mechanisms and software, however, cannot serve as a justification for the breach of financial sanctions.

The recent Ukrainian crisis provides a good example of the difficulties that financial institutions are facing. The asset freeze obligations, which require the freezing of funds and economic resources of listed persons and entities and prohibit making such funds and economic resources available, raise several questions of interpretation and application. What is and what is not indirectly making available funds to or for the benefit of a designated person? Are credit institutions holding funds that were handled as collateral required to cease their activities in relation to these funds or should they obtain prior authorization? Do financial institutions retain their right of set-off?

The sectoral sanctions against Russia, which include restrictions on access to capital markets by imposing a ban on the purchase, sale, and provision of investment services, and on dealing with transferable securities and money-market instruments, represent another manifestation of financial sanctions. Again, the implementation of the measure has proven to be arduous. Do promissory notes or bills of lading come within the scope of the restrictions? What behaviors are covered by the prohibition to directly or indirectly make or be part of an arrangement to make new loans or credit? Is one supposed to aggregate the proprietary rights of different sanctioned entities when determining whether an entity is owned 50% by a listed entity?

Mindful of the difficulties faced by its numerous financial institutions, the Luxembourg Ministry of Finance has recently provided useful and up-to-date guidelines on the implementation of financial sanctions against third countries, entities and private persons (click here, only available in French). Professionals will find in these guidelines the definition of essential terms such as “funds”, “asset freeze”, “making economic resources available” or “designated legal entities”, provided by reference to the different Guidelines (click here) and Best Practices (click here) documents of the Council of the European Union. The latest Commission guidelines on the financial sanctions are dated 25 September 2015. There is also an earlier 2014 set of guidelines on financial sanctions. Practical information on how to comply is also provided, together with a list of red flags and of the competent authorities.

The United Kingdom decided to complete this approach, by including in its recently published guidance on financial sanctions (click here) different lists of frequently asked questions. Interestingly, the questions reported are sorted on the basis of the quality of the persons or institutions asking them, such as the designated persons themselves, their friends and family, but also lawyers and, in particular, financial institutions.

Several documents were also published by the European Commission. Of particular importance is the Commission’s notice on the implementation of Regulation 833/2014 (click here), which provides detailed answers on the application of the sanctions against Russia. Other documents provide general FAQS on the restrictive measures (click here), or take the form of in-depth information notes (click here).

Whatever explanation and guidance is provided, however, it seems that open questions will remain part of the sanctions regimes, in particular financial sanctions. In addition to the difficulty of keeping up with the fast changing regulations and understanding their provisions, compliance has become quite challenging because of the existence of corporate structures that lack the required transparency.

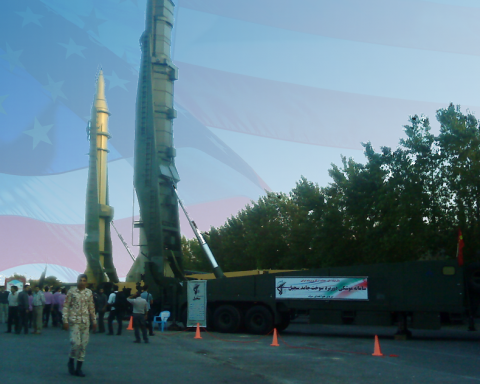

Offshore companies registered in certain jurisdictions can make it difficult – sometimes impossible – to determine the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) of a corporate structure. Such a lack of transparency makes a most unwelcome tool for circumventing the embargos and financial sanctions imposed by the US, UN and the EU. This mechanism is known, for instance, to have allowed a bank, linked to the then sanctioned Iranian Government, to own a skyscraper located in the heart of Manhattan.

This practice adds to the difficulty of complying with the financial sanctions. Even renowned (Luxembourg) financial institutions, following first class best practices and due diligence, experience trouble in identifying the UBO. The Know-Your-Customer, due diligence and other screening mechanisms are put to a severe test, the reliability of which will have to be assessed on regular basis.

Co-authors of this post are:

- EU to Amend Union General Export Authorization in the Event of a No Deal Brexit - January 29, 2019

- Adoption of New EU Legislation and Recent National Cases in the Fight Against Chemical Weapons - October 24, 2018

- Shipping Criminal Liability: the Difficult Position of the Transportation & Logistics Sector - January 4, 2018